Chinese politics under Xi Jinping

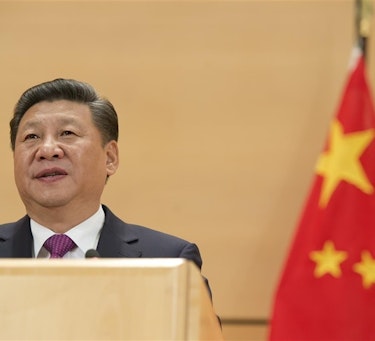

Xi Jinping speaking to the UN at Geneva.

Foto: UN/Jean-Marc Ferré (CC BY)This week's analysis is written by Hans Jørgen Gåsemyr, Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Bergen and Senior Researcher at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI). Gåsemyr writes about the proposed removal of term limits for the presidency of China.

The news about China’s top leadership wanting to scrap formal limitations on presidential terms is making waves. While many observers are deeply concerned by an increasingly authoritarian and strongman streak in Chinese politics, reactions inside China are more diverse, albeit muted. Xi Jinping, who is both China’s President and Communist Party chief, enjoys broad support, but is also controversial, which strong and effective leaders tend to be.

China is at a critical moment in its modern history. The economy is in the midst of a complex transformation. Social security reforms, environmental policies and military modernization require massive investments and oversight. China is becoming both more assertive and engaged in international politics. It is not shocking that many Chinese – inside and outside the Party – are willing, even hoping, to see a strong leader like Xi carry on. It is equally understandable that others are expressing genuine fear. China’s history of state leaders amassing unchecked powers and causing disaster is rich.

China’s constitution stipulates a maximum two five-year terms for any one president. That is evidently not enough for Xi, who has proven extremely effective at consolidating power and support. Many have suspected he would hold on to power, in some form, beyond two terms. Now that expectation is written out in a law-revising proposal, to be decided by China’s legislative body, the National People’s Congress, in early March.

Xi rose to the highest level of Chinese leadership in 2012, when he became General Secretary of the Communist Party. Simultaneously, he was put in charge of the Party-ruled Central Military Commission, which effectively controls the armed forces. Then, the following spring, he was elected President of China, or “Country Chairman” (Guojia zhuxi), as the Chinese title reads. It is the formal rules surrounding the presidency that is now likely to change, and by all measures, the presidency is the least important among the three positions. Still, if the door to an endless presidency opened up, would the other positions follow?

There are no formal restrictions, but several informal norms, for how long a person can lead the Party or the Military Commission. Top leadership positions within the Party are also supposed to last no longer than two five-year terms. Persons reaching the age of 68 are expected to retire, not begin a new term. These arrangements are supposed to ensure rotation, renewal, and consensus-based leadership, while preventing any one person or group from amassing too much power. If Xi, who is already 64, remains the Party’s top official beyond two terms, that is a considerable departure from principles that have guided Chinese politics over the last two or so decades.

We do not know how this may and may not play out. Even if the clause on presidential term limits is scrapped, Xi would have to be elected, or at least approved, by the national legislature. Within the Party, he would need continuing, active support by his peers. These conditions are not easy to meet. Divisions and interest factions within the Party are still alive and may start kicking, even if Xi maintains decisive authority. Could it be that Xi envisions a presidential role for himself without holding on, at least formally, to the highest Party positions? Unlikely, perhaps, given that most power is vested there. For now, we are left to speculate.

Further reading:

Hans Jørgen Gåsemyr (2016) Fem kritiske år for Kina (Norwegian) ("Five critical years for China")

Tony Saich (2017) What does General Secretary Xi Jinping dream about?

Frank Tang and Jane Cai (2018) Is keeping Xi Jinping in power the answer to China’s economic woes or a recipe for disaster?

Hans Jørgen Gåsemyr is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Bergen and a Senior Researcher at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), with Chinese politics and society as his main research areas.