The 2021 Elections in The Netherlands

The People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), led by acting Prime Minister Mark Rutte, is set to win the elections. Rutte is currently serving in a demissionary capacity after his resignation on January 15, 2021.

Foto: Raul Mee / Flickr (CC BY 2.0)The Netherlands goes to the polls to elect a new government on March 15, 16 and 17. In this week's analysis, Professor of political science at NTNU, Pieter de Wilde, discusses some of the more interesting aspects of the election from a Norwegian point of view.

On 17 March 2021, The Netherlands goes to the polls for Tweede Kamer (second chamber) elections. Like Norway, The Netherlands is a parliamentary democracy and constitutional monarchy. The Prime Minister and his or her government are dependent on a majority in parliament for governing, while King Willem Alexander performs only a ceremonial role. The Netherlands has an elaborate welfare state, like Norway. As is the case with Norwegians, Dutch people are culturally strongly oriented towards the Anglo-Saxon world. Almost everyone has strong command of English as a foreign language. Very few speak any other foreign language. It has a multi-party system with many similarities to the Norwegian party system. Box 1 provides an overview of the main parties, their expected vote share at the time of writing, and which Norwegian political party comes closest in terms of ideological profile. In many ways, therefore, politics in The Netherlands is very similar to politics in Norway. There are a few notable differences, however.

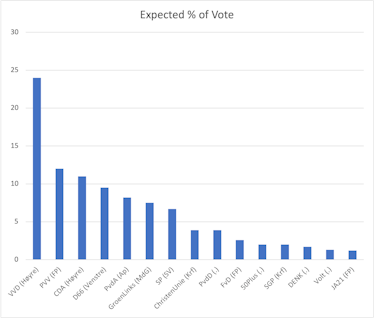

Box 1: Expected percentage of vote by political party. Norwegian ideological relatives in brackets. Source: www.peilingwijzer.nl, 9 March 2021.

First, The Netherlands has an electoral system of pure proportional representation. Israel and The Netherlands are the only two countries in the world with such an extreme proportional representational system. At stake are the 150 seats in the Tweede Kamer, the entire country is a single electoral district and there is no threshold in terms of a minimum percentage of votes a party needs to get before being eligable for seats in parliament. This means that any party receiving a minimum of 0,67% of the total nation-wide vote will get representation in parliament. The result of this pure proportional representation system is that a lot of parties compete in the election and many receive sufficient votes to get representation. During this 2021 election, a total of 37 different political parties are on the ballot. This is a post-WWII record. At the time of writing, a week before the election, polls indicate that 15 of these parties will get seats in parliament.

Like most European countries, including Norway, recent decades in The Netherlands feature a process of party fragmentation. The main Christian democratic (CDA), liberal (VVD) and social-democratic (PvdA) parties that dominated the political landscape during the 20th century are getting fewer votes. Where the three of them together could count on about 80% of the vote during the 1950s and 60s, they are now expected to receive around 45% of the vote. Challengers to these three classic parties include socialist and pacifist parties, neo-fascists, social-liberal parties, environmental parties, far right populists, and many others.

The pure proportional representation system makes The Netherlands somewhat of a laboratory for party politics in Western Europe. If you’re thinking of starting a new political party here in Norway and wonder whether it has a shot at electoral success, I advise a look at Dutch elections. Chances are your idea has been tried there already. Allow me to just provide a very brief overview of some of the more interesting political parties, from my perspective. DENK is a party created by former MPs of the social-democrat PvdA, of Turkish origin. It has developed into a party for conservative Muslims in The Netherlands, campaigning hard against discrimination, anti-Islamism and far right populism whilst defending conservative cultural traditions within the Dutch Muslim community, particularly of Turkish descent. Its relationship to Erdogan’s government in Turkey and to extremist mosques in The Netherlands with Gulf state funding has been questioned. Volt is the first truly pan-European party campaigning on a European federalist agenda. The Partij voor de Dieren (Party for the Animals) campaigns on animal rights and nature preservation from a more religious perspective than the environmentalist party GroenLinks does. 50PLUS campaigns on pensioners’ interests, presenting itself – as the name indicates – as the party for people over 50. Now I am just mentioning a few of the parties that are expected to be among the 15 that will get representation in parliament this election. For more excentric examples, one could look at the 22 parties that are also participating, but will likely not receive sufficient votes to gain a seat in the Tweede Kamer, or the many parties that have competed during recent elections but failed to get enough votes for representation.

The plenary hall of the Tweede Kamer ("Second Chamber"), the Dutch Parliament.

Foto: Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)The cultural dependency on the Anglo-Saxon world has important political connotations. The Black Lives Matter and Me Too movements have come to play a role in The Netherlands too, especially since The Netherlands is a former colonial power and thus has a significant minority of African descent. Bij1 is a political party campaigning solely against institutional racism. Female candidates of all parties, but especially parties on the left, receive disproportionate sexist abuse on social media during the campaign. This import of recent American culture wars likely results in extra votes for female candidates and cosmopolitan political parties on the one hand and for parties campaigning against too much ‘wokeness’ on the other hand. The Netherlands has also imported conspiracy theories from the US. In no other European country does the QAnon theory have as many supporters as in The Netherlands. The BBC recently published a short story on Dutch protests against Corona measures and the role of QAnon in the upcoming elections. The story needs to be taken with a grain of salt, however, as it is part of the BBC’s desperate attempt to legitimize Brexit by pretending things are even worse in other European countries. I worry such stories about the Dutch elections will get disproportionate coverage in Norway because Norwegian journalists – like their Dutch counterparts - are so dependent on English language sources for foreign news. Yet, even if support for conspiracy theories numbers only in the 10s of thousands, it is still a worrisome development.

Conversely, pure proportional representation breeds both volatility and stability. A scenario where a far right conspiracy theorist becomes President is unthinkable. The upcoming Dutch elections are likely to be rather boring. Like in most European countries nowadays, the electorate is divided into three more or less equally sized groups: the left, the center-right, and the radical right. Voters change their minds within those three big groups, but rarely shift between blocks. The result is stability. The leading VVD party of Prime Minister Mark Rutte is all but certain to again become the biggest party and will have to form a coalition to govern. That coalition is likely to include the other major center right parties and either one or two of the more moderate leftist or more moderate radical right parties. It has been like that for over a decade.

The Norwegian Atlantic Committee frequently presents a time-relevant analysis, handpicked by one of the Committee's partners, employees or others. If you want to write the next 'Weekly analysis', contact kristoffer@dnak.org. The content of the analysis does not necessarily represent the official view of the Norwegian Atlantic Committee.